| March 5, 2008 |

A few months ago, in a piece entitled "Subprime Geopolitics," we addressed two questions. The first was whether the U.S. economy was heading into recession. The second was whether such a recession would represent anything more than the normal business cycle, or whether it would represent a fundamental, long-term shift in the way the American economy works. We answered that while the economy could reasonably go into recession-and we would not be surprised if it did-in our view, a recession did not seem imminent. As for whether such a recession would represent a fundamental shift in U.S. economic life, we answered, no, this would not be "the big one."

Americans have been waiting for the big one ever since 1929. In many ways, the Great Depression should not have come as a surprise. Some sectors of the U.S. economy-particularly agriculture-had been in a depression for years, and the global economy was deeply troubled. Nevertheless, there was a sense of euphoria in the 1920s, unjustified by circumstances. Indeed, euphoria is the classic sign of an economic peak, and one of the warnings of an impending collapse.

Still, the market crash-followed by a prolonged depression-stunned the country and permanently scarred it. The contrast between the euphoric expectations of the 1920s and the grim reality of the 1930s imbued Americans with a fundamental fear. That fear is this: Underneath the apparent stability and prosperity of the economy, things are terribly wrong, and there suddenly will be a terrible price to pay. It is the belief that prosperity is all an illusion. This was true in 1929, and the American national dread is that 1929 is about to repeat itself. Every recession evokes the primordial fear that we are living in a fool's paradise.

There is now an emerging consensus that the United States has entered a recession. In a technical sense, this may or may not be true. Whether the economy will contract for two successive quarters or be considered a recession by some other technical measure, clearly the U.S. economy has shifted its behavior from the relatively strong expansion it has enjoyed for the past six years.

But whether there is a recession now is not the question. Rather, the question should be whether what we are experiencing is a cyclical downturn on the order of 1991 or 2001-which were passing events-or whether the economy is entering a different pattern of performance, a shift that could last decades. The dread of hidden catastrophe is one thing. Quite another thing is whether the economic expansion that began in 1982 and has lasted more than a quarter-century is at an end. But whether there is a recession now is not the question. Rather, the question should be whether what we are experiencing is a cyclical downturn on the order of 1991 or 2001-which were passing events-or whether the economy is entering a different pattern of performance, a shift that could last decades. The dread of hidden catastrophe is one thing. Quite another thing is whether the economic expansion that began in 1982 and has lasted more than a quarter-century is at an end.

The United States has had three economic eras since World War II. The first was the period from about 1948 until about 1968. It was marked by tremendous economic growth and social transformations, rising standards of living and cheap money. Then, there was the period between 1968 and about 1982. This period was marked by intensifying economic problems, including much slower growth, increasing commodity prices, high interest rates and surplus labor. The third period, which began in 1982, saw extremely high growth rates, rapid technological change, increasingly cheap money and low commodity prices. The first era lasted 20 years. The second lasted 14 years. The third has lasted 26 years. None of these eras moved in a straight line; each had cycles. But when we look back, each had a distinct character.

The important question is this. Have we really been in a single era since 1948, with the 1968-1982 period representing merely a breathing space in a long-term, multigenerational expansion? Or are we in a period of alternating eras, in which expansionary periods alternate with periods of relative dysfunction and economic stagnation?

If the former, then 1968-1982 was simply a period of preparation for an intensification of the 1948-1968 era, and the extremely long 26-year cycle makes complete sense: The United States has just resumed the long-term growth of the first era. If we are stuck in alternating eras, however, then the 26-year cycle is overdue for a profound cyclical shift. In confronting this question, of course, we are not only talking about the United States; we are talking about the very structure of the international system. If the United States periodically will be shifting into periods such as 1968-1982, we are facing a very different world than if the United States is in a long-term expansion with shorter down cycles.

To answer this question, we need to consider why the United States underwent the 1948-1968 expansion in the first place. To begin with, the United States has been in a massive economic expansion since about 1880. The basis of that expansion was the massive inflow of labor through immigration coupled with intense foreign investment. That plus American land completed the triad of land, labor and capital.

In a world of expanding population, the demand for American industrial and agricultural products always grew, as did the available labor force. The gold standard put in place at the time the American expansion began also accelerated the process by encouraging domestic investment and limiting consumption. Indeed, it was this combination that temporarily caught up with the United States in 1929: Surplus capacity combined with a shortage of demand and credit crippled the economy.

World War II, not the New Deal, began solving the problem by using the industrial and agricultural plant while constraining consumer demand due to war production. It put people back to work and put money into their hands-money that could not easily be spent during the war. The war also created two other phenomena. The first was the GI Bill, which created massive credit supplies for veterans buying homes and cheap or free educations, increasing the quality of the labor pool. The children and grandchildren of immigrants became professionals, able to drive the economy through a variety of forms of increased productivity.

The second phenomenon was the Interstate Highway System. That not only increased economic activity in itself, it decreased the cost of transportation, making hitherto inaccessible land usable for homes and later businesses. While the system devastated the inner cities by shifting population and business to the newly accessible suburbs, the availability of cheap land allowed for a construction boom that went on for decades. You could now live many miles from where you worked, which led to two-car families and so on. So where the expansion in 1880 was heavily dependent on foreign labor, capital and markets, the expansion in 1948-1968 depended instead on domestic forces.

The first postwar era (1948-1968) also was driven by deficit financing during World War II and the creation of consumer credit systems; it was then disciplined by somewhat tighter economic policies in the 1950s. The basic principle remained encouraging consumption. This led to the use of the existing industrial plant, thus putting people to work in it and in building new businesses.

The era ran out of steam in a crisis of overconsumption and underinvestment. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the desire to stimulate consumption created massive disincentives for investment. Low interest rates and high marginal tax rates shrank the investment pool. As time went on, the industrial plant became less modern and therefore less competitive globally. Demand for money drove interest rates up, while the inefficiency of the economy drove inflation.

Moreover, the baby boomers became adults and began to use credit and social services at an increasing rate. Using an increasingly undercapitalized industrial plant meant greater inefficiency as usage increased. Inflation resulted, paradoxically along with unemployment. The attempt to solve the problem through techniques used in the first era-more credit and more deficit spending-ultimately created the crises of the late 1970s and early 1980s-high interest rates, increased unemployment and high inflation.

The third era began when high interest rates forced massive failures and restructurings in American business. The Gordon Gekkos of the world (for those who have seen the 1980s movie "Wall Street") tore the American economy apart and rebuilt it. Global commodity prices fell simply because the money not being invested in the United States was being invested in primary commodity production since the prices were so high. Therefore, they plunged inevitably. Finally-and this will be controversial-the Reagan administration's slashing of the marginal tax rate increased available investment capital while increasing incentives to be entrepreneurial. Low marginal tax rates weaken the hand of existing wealth and strengthen the possibility of creating new wealth.

This kicked off the massive boom that emerged in the 1990s. It drove existing corporations to the wall and broke them (Digital Equipment) and created new corporations out of nothing (Microsoft, Apple, Dell). The highly capable workforce, jump-started in the 1950s by the GI Bill, evolved into a large class of professionals and entrepreneurs. The American economy continued to rip itself apart and rebuild itself. America was indeed the place where the weak were killed and eaten, but for all the carnage of the U.S. economy, the total growth rate and the rise in overall standards of living were as startling as what happened in the first era.

Now we get to the big question. The first postwar era culminated in a crisis of overconsumption and underinvestment that took almost a generation to work through. Are the imbalances of the last quarter-century such that they necessitate a generational solution, too, or can they be contained in an ordinary recession? Behind all of the discussions of the economy, the question ultimately boils down to that. To put it another way, the first era contained many leftover structural weaknesses of the Great Depression. It could not proceed without a pause and restructuring. Was the restructuring of the second era sufficient to give the third era the ability to proceed without anything more than an ordinary recession?

There are certainly troubling signs. The return of commodity prices to real levels last seen in the late 1970s is one. The size of the U.S. trade imbalance with the rest of the world is another. Most troubling is the relative decline of the dollar, not so much because it directly affects the operation of the American economy but because it represents new terrain. When we take all these things together, it would appear that something serious is afoot.

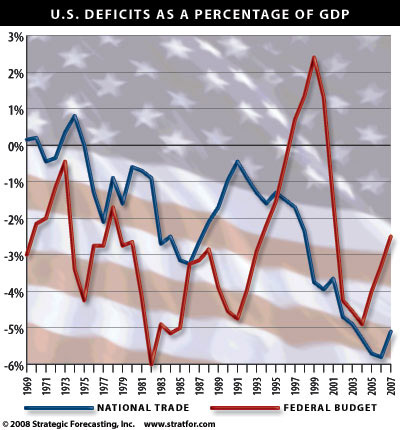

But there are the things that are not troubling, too. In spite of high commodity prices for several years, the inflation rate has remained quite stable. Interest rates have moved around, but actually are quite low, certainly by the standards of the 1970s when mortgage rates were in the high teens. The budget deficit in 2007 ran at 2.5 percent of gross domestic product, which is not any bigger than it has been since those Reagan tax cuts. Unemployment is higher than it was, but certainly is not soaring. And we are not seeing any of the combination of conditions we saw in the late 1970s, nor any of the conditions that led Richard Nixon to impose wage and price controls in the early 1970s.

The most remarkable thing is the ability of the U.S. economy to absorb record-high oil prices without going inflationary. This is because oil consumption in the United States today is not much higher than it was in the 1970s. It is not simply a matter of efficiency; it is also a reward for de-industrialization. By shifting from an industrial to a technological/service-based economy, the United States insulated itself from commodity-driven inflation.

The key to the U.S. economy is the service sector-which comprises everything from computer programmers to physicians to Stratfor employees. The service sector has high levels of productivity driven by technology. Productivity continues to grow, which is not historically what you would find as you enter a recession. So long as productivity grows and inflation and unemployment remain under control, the total wealth of a society increases. The transformation of the economy that occurred as a result of the pain of 1968-1982 is creating a situation in which massive economic disequilibrium has not yet interfered with productivity growth. The historical hallmark of the beginning of a recession is declining productivity due to overutilization of the economy. Productivity continues to rise. And that means, in the long term, wealth will continue to rise.

As a result, while disequilibriums in the financial system require serious recalibration that must limit growth or even cause a decline, it is our view that we are not facing an end to the expansion that began in 1982. The old dread that this is the big one, the depression we all deserve, is actually a positive sign. The dread causes caution, and caution is the one thing that can control and shape a recession, since lack of caution is usually the proximate cause. Therefore, the effects of the changes forced in the second postwar era remain intact. The financial crisis is cyclical. And growing productivity rates indicate that while this will hurt like hell, it is not the big one-it is not even going to be like 1982. This is 1991 and 2001 all over again.

Stratfor is a private intelligence company delivering in-depth analysis, assessments and forecasts on global geopolitical, economic, security and public policy issues. A variety of subscription-based access, free intelligence reports and confidential consulting are available for individuals and corporations.

Click here to take advantage of 50% OFF regular subscription rates - offered exclusively for BillOReilly.com readers. |

| Posted by George Friedman, Stratfor.com at 11:37 AM |

| Share this entry |

|

|

|

|