One hundred years ago on the plains of southwestern Kansas, a storm was brewing. But it was not one bearing rains to support the area's residents, nor would it bring the winds and dust that would ravage the same land less than two decades later. Instead, a microscopic clump of proteins, genetic material, fats and carbohydrates was shaping up to cause the worst global disease pandemic in modern history: In the span of about a year from 1918 to 1919, the Spanish influenza killed an estimated 20 million to 50 million people around the world. Many factors that contributed to the outbreak's severity were unique to their time. The wartime world was more connected, allowing the virus to spread faster than ever, but the still-nascent understanding of how diseases worked meant that sanitation guidelines and treatment methods were lagging. Meanwhile, World War I had ravaged economies and populations across the globe and contributed to media censorship that limited the dissemination of information about the disease.

Since then, vaccines and medicines have been developed to fight diseases of all sorts. Moreover, people now can more closely monitor the spread of disease through social media and the 24-hour news cycle. And yet, the influenza virus, with its ability to rapidly mutate and adapt, remains one of the world's greatest disease threats. Each year, the flu virus kills thousands and poses tens of billions of dollars in treatment costs and equivalent amounts in economic losses in the United States alone. Countries and corporations have long been working to develop a universal vaccine that targets all strains of the flu, and in the coming years, these efforts will continue alongside the increased focus on data sharing, social media and blockchain — all key tools for disease outbreak control. In this way, the flu exists at the intersection of geopolitics and disease. Indeed, as countries continue trying to regulate developing technological sectors, they will also, perhaps inadvertently, effect how diseases are monitored, controlled and contained.

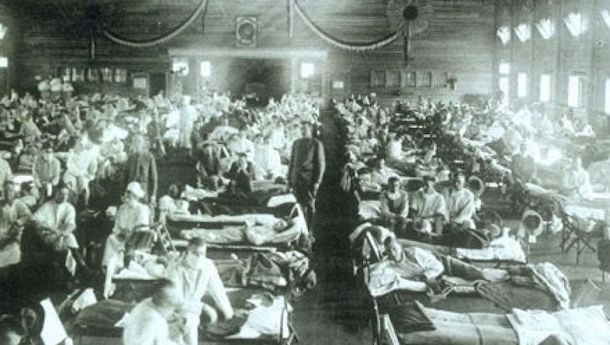

As December 1917 faded into 1918, World War I raged on, providing perfect breeding grounds for multiple diseases. Training camps and hospitals brimmed with soldiers from around the world, while those on the front lines languished in deplorable conditions. Yet author of The Great Influenza John M. Barry suggests that what would become known as the Spanish flu first emerged in the civilian community of Haskell County, Kansas, in January 1918. Historians may never be certain of its exact origins, but Barry postulates that the disease spread to the nearby Camp Funston military training grounds in the spring, before U.S. troop deployments took it global. The flu did not acquire its moniker until it hit the shores of Spain, a country not at war and therefore more open about recording the presence of the disease in its media. By the fall of 1918, the war was nearing its end, but the flu was at full force, targeting the healthy as well as the very young and old. It had infected hundreds of millions by the time it waned in 1919.

Vaccines, antiviral medication, improved sanitary measures and generally better medical care have dramatically decreased the threat of the flu in the last century. However, the race against evolution continues: None of these advances have been able to completely combat the rapidly evolving nature of the disease. The flu that hit in 1918 was a strain of H1N1, but there are dozens of possible flu types that can arise from combining the proteins on the outside of the virus called hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). So far, scientists have identified 18 types of hemagglutinin and 11 types of neuraminidase — any combination of which yields a new and unique flu, from H2N2 to H3N2 to H5N1 to H7N9. Mutations can alter the severity of the illness and limit the effectiveness of existing treatments year after year.

To cause a new pandemic, the virus would need to mutate into a form that makes it transmittable among humans, easily spread and very deadly. The emergence of a flu strain with this trifecta of traits is unlikely, but given the interconnectivity of the current world, if one did, the risks of widespread contagion would be high. And even the most pedestrian flu seasons exact a death toll in the thousands.

The CDC recently changed the topic of its Jan. 16 meeting from nuclear war preparedness to the flu.

A Flu Season Fit for an Anniversary

While unlikely to reach pandemic levels, the 2017-2018 flu season has gotten off to an early and vigorous start. Australia, where the flu season typically runs from April to September, has historically been a harbinger of the severity of each year's emergent strain of influenza elsewhere. This year's vaccine did little to prevent the spread of the virus in the country, leading many to accurately predict a brutal 2018 flu season for those north of the equator. In the United States, a high number of infections has prompted schools to close in some places and hospitals to institute visitation limits; so far, only Hawaii has not experienced a widespread number of flu cases.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that this year's flu vaccine has been effective in only 32 percent of the population. Additionally, the type of virus that is dominant in the United States this year, H3N2, typically causes more severe symptoms than other common strains. These factors together have caused mortality rates for this year's outbreak to reach epidemic levels throughout the country, according to the most recent CDC update. In response, the CDC recently changed the topic of its Jan. 16 meeting from nuclear war preparedness to the flu.

One hundred years removed from the global pandemic, there is still work to be done in the fight against the flu. While current vaccines typically target the parts of the flu virus that change year to year, firms such as the Alphabet Inc.-funded Vaccitech are working to develop a "holy grail" vaccine that targets the parts that do not easily mutate. Vaccitech hopes to have a universal vaccine, which would boost efficacy rates over current approaches, ready by 2025. In December, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) removed a three-year ban on funding for "gain of function" studies, in which researchers study mutations that change how viruses work, including those that cause Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Ebola and influenza. Funding from an institution as large as the NIH is another major factor in helping scientists stay one step ahead of viruses, and it could eventually aid in the creation of flu vaccines or treatments for new strains.

New Rules for New Tools

Developments in technology — particularly in the area of data science, which can allow researchers nonmedical avenues for tracking diseases and preventing their spread — are crucial in the ongoing fight against disease outbreaks. A recent paper in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, for example, outlined how Facebook could be used to track and target human bridges of transmission. By identifying individuals who act as hubs for the spread of disease, medical professionals could more effectively and efficiently distribute limited vaccines in the event of a widespread outbreak. Other social media outlets all have the potential to play a similar role. Meanwhile, blockchain technology, which allows for the storage of massive amounts of personal data, also offers opportunities for tracking the spread and risk of diseases such as the flu. It would not only allow the efficient transmission and sharing of data — it would enable users to maintain privacy standards, a quality that will become increasingly valuable in the future.

The use of these and other technological advancements to help with disease control may face policy roadblocks, as data sharing and data privacy become key topics of political discussion. As the world becomes ever-more digital, and the amount of available data to analyze increases, governments will diligently focus on developing regulations for how that data is shared. Already, countries the world over are prioritizing intellectual property and digital rights in trade negotiations.

Data sharing and collection is vital for the understanding of disease; indeed, some experts attribute the severity of the SARS outbreak in 2003 to a lack of communication between Beijing and the rest of the world. But in the future, strict regulations developed by countries trying to protect their citizens' privacy may hamper communication efforts. In 2016, for example, the European Union instituted the General Data Protection Regulation, which gave its citizens greater control over how their personal data is shared and distributed. Perhaps more importantly, this new privacy law also permits countries to fine companies found in violation. Of course, the intent of such laws is not to prevent helpful medical communication, but rather to prevent the distribution of private information. But they could still delay the global implementation of these kind of technologies for epidemiological purposes, as governments try to sort out how and when to make exceptions for the medical community.

In the 100 years since the Spanish flu reached even the most remote corners of the globe, society has made countless improvements as it learns more about the science of disease. But though people are better equipped to treat victims and limit the spread of viruses with vaccines and other medicines, the risk of a global pandemic remains. Emerging technologies provide valuable tools for advancing disease control, but policy and regulation have the potential to limit or delay their impact. At the intersection of health, technology and geopolitics, the regulation of data policies have the ability to stir up storms that can spread far beyond Silicon Valley.